Sculpting in Digital Space

Sculpting in Digital Space

PUBLIC LECTURE & COFFEE

Performing Encryption and Conspiracy Archives

two artistic encounters with digitization and movement

memory

Sept 27th, Thursday | 9:00 - 10:00 am

Motion Lab | 350 Sullivant Hall

In this talk Susan Kozel will discuss two artistic collaborations to emerge from the Living Archives Research Project. Both projects are collaborations between dancers and digital artists, revealing divergent ways to materialize traces of bodies in motion. Instead of presenting standard ‘legible’ archives, these projects play across clarity and ambiguity, somatic resonance and affective transmission. "Performing Encryption" is a collaboration with artist duo Gibson / Martelli and "Conspiracy Archives" is a Mixed Reality installation based on the work of choreographer Margret Sara Gudjonsdottir (with visuals by Jeannette Ginslov).

Professor Kozel’s scholarly and artistic work is located at the convergence between philosophy, dance, interaction design and new media. She is a Professor in the School of Art and Culture at Malmo University, Sweden. She has an international profile as a contemporary phenomenologist who applies philosophical thought to a range of embodied practices in the context of digital media technologies. Her research takes the form of both scholarly writing and performance practices. Current research foci are affect, re-enactments and somatic archiving. She is the author of Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology (MIT Press 2007) and affective Choreographies (forthcoming).

Hosted by Humane Technologies a pilot project of the Global Arts and Humanities Discovery Themes at The Ohio State University, Advanced Computing Center for the Arts & Design (ACCAD)

At the heart of our approach to humane technology is prioritizing bodily and multisensory experience in our relationship with computing environments. Scott and Kyoung Swearingen’s tackles this head-on through meaningful integration of digital and physical experiences in game play. They are especially interested in collaborative play that is human facing and contributes to everyday wellbeing. They seek to create experiences that makes people more connected through face to face interactions and not exclusively face to screen game play. Scott explains, "the humane tech collaboration has helped me and Kyoung realize how important physicality is to our work, not just materials but our bodies and meaningful social engagement through play. I think we always valued this but now we have a clearer mission, vision and language for what we are doing and a bunch of great collaborators!"

Wall Mounted Level

As a creative team, they got involved in first year of Humane Technologies project in research sandboxes and through their work with other collaborators were drawn to the notion of physical/digital play. From that collaborative exchange they invented the piece Wall Mounted Level, which is an engaging (and award winning) game but also Stephen Turk, a member of the Humane Tech team from the Knowlton School of Architecture noted that this approach has enormous potential for the future of architectural models and presentation. If you can create physical models and move digital characters through them then you have a much more dynamic representation of the architectural vision and research.

On their website the Swearingen's describe Wall Mounted Level as "a collaborative, multiplayer game that is projected onto a hand drawn cityscape that was laser-cut and assembled into a relief sculpture. Using projection-mapping and other compositing techniques, players move their characters into, out of, and across the fractured environment that doubles as a metaphor for conflict in their internal landscapes. Our motivation for creating ‘Wall-Mounted Level’ was to embrace tangible surfaces as mediums for games to exist in, and for the interactions between players to occur in person. The verbal communication and physical touch that takes place between the players is especially important to us in terms of human-facing interactions as it extends the games narrative of ‘reconciliation’." Scott Swearingen explains "'Wall-Mounted Level' meets two goals of Wizaga head-on, we are using real, physical surfaces for our environment to enhance a sense of presence and promote empathy and these human-facing interactions promote 'meaningful choice'." Check out a video of the gameplay here.

Their Physical Scroller game that they created in Pop-Up 2017: Livable Futures was a collaboration with ACCAD alumni Ben Schroeder and J. Eisenmann who we invited back to work with us for the week. Together they put together a depth sensor with a top-mounted projector to create a cooperative multiplayer game that not only invites but requires physical and verbal coordination to successfully navigate hazards in a life-size vertical scroller. Scott shares that "the goal of the game is simple: players navigate the red ball through a field of vertically scrolling hazards until reaching the end of the level. A depth sensor tracks the median position of all player ‘blobs’ and places the red ball there. There are options however! Because the depth sensor only registers at a specific altitude around shoulder-height, players can duck beneath it, effectively removing themselves from play. The result is a ‘pass’ to the other players. Additionally, spreading your arms out and making yourself a ‘larger blob’ increases your area of influence and biases the red ball in your direction - this helps tremendously when finessing the red ball around obstacles. It is simple but fun!" Here's a video.

Overall these game designers are seeking to include the body more in digital gaming and creating real time interactions which led yet another series of collaborative works, this time with artist Rosalie Yu or was a guest artist for Humane Tech in 2016, Currently, they are prototyping a pop-up book that combines tactile physical interactions and augmented digital characters which move around the space through the phone. The project has an experiential, discoverable quality and users can walk around the book to gain new views of the landscape. The phone becomes a window to see the story come to life. The team is passionate about using augmented reality (AR) because it can be a gateway between two generations since AR is so intuitive and can effortlessly combine the tactile experiences with the technology in what many expect our future to become, an ever more mixed space of digital and physical realities enterwining.

At this year’s Wellbeing Pop Up 2018, Scott and Kyoung met Susan Thrane from the College of Nursing and they have started another collaborative project entitled Circle. This game designed for children with cognitive and physical disabilities and individuals in palliative care. Stay tuned for more info!

Scott and Kyoung are committed to collaborative play and are collaborative makers who consistently, through Humane Technologies events and in the larger field, create exciting experiences to enhance the players experience and create more livable futures.

Documentation of Kevin Bruggeman, Skylar Wurster, and Susan Melsop's project Virtual Healing Spaces is now live on the Humane Technologies Media Gallery! Check out the work below:

Virtual Healing Spaces is a meditative experience in Virtual Reality designed for stress reduction and mindfulness. The experience combines mind body centering methods and technology to create a bridge from traditional meditative practices to an enhanced VR environment.

Reflection contributed by Dan Shellenbarger

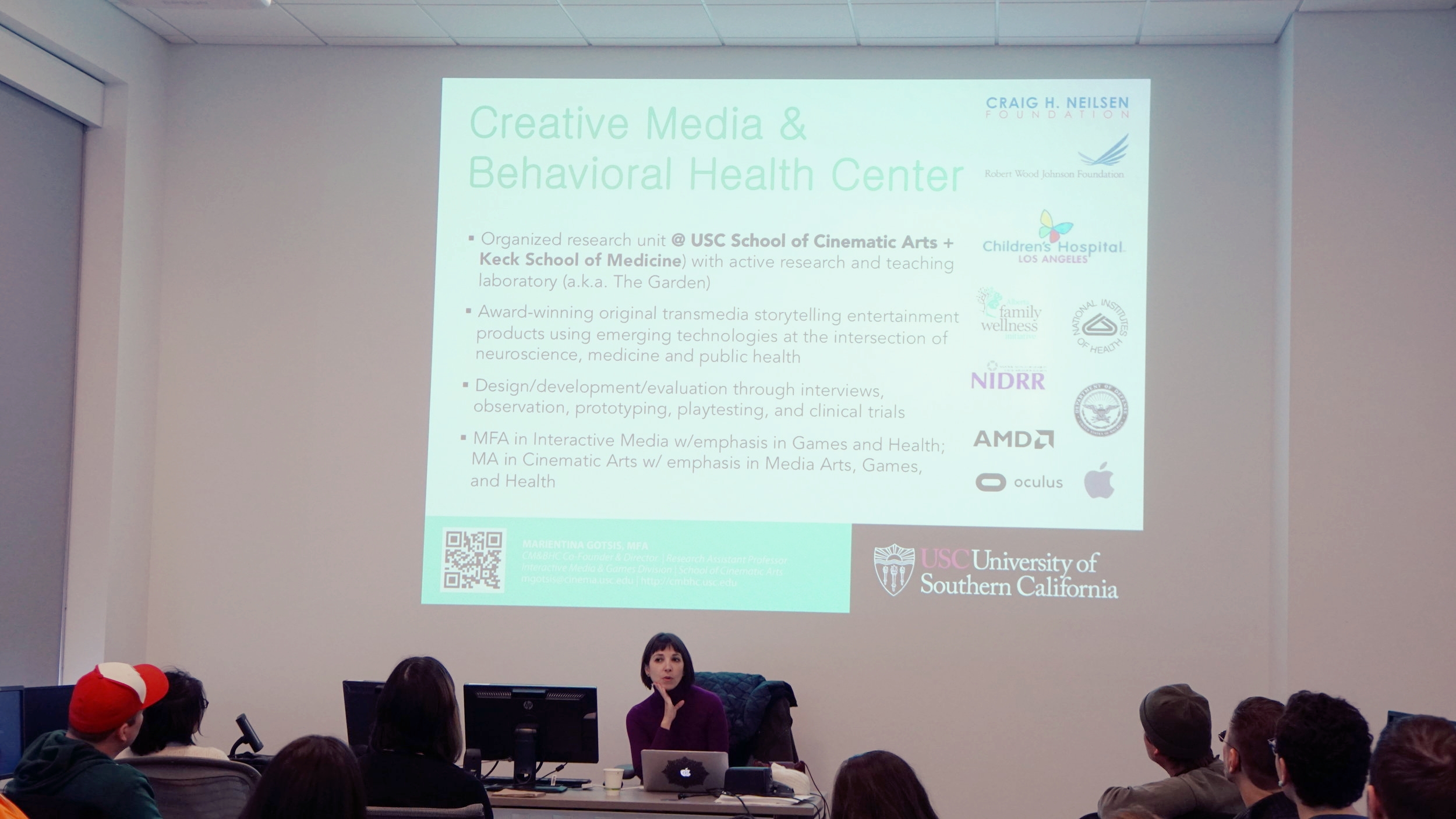

Marientina Gotsis shared her work and research during her flash presentation for the Humane Technologies Conference. She founded and currently directs the USC Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center, where she also founded and directs the USC Games for Health Initiative. Her work involves translating interactive media innovations to health practitioners. She works works to intersect art, neuroscience, medicine, and public health.

She showed projects that were developed to help in the research fields including Parkinson's and mental health. In the area of mental health she share a quote from Jaak Panksepp, a neuroscientist, who provides an inspiration to her work:

“Mental health ultimately means that an individual, through rich emotion-affirming encounters with living, has integrated his or her life in such a way that the emergent self-structures, deeply affective, can steer a satisfying cognitive course through future emotional jungles of lived lives.”

In her work and the work that is developed in the USC center, she is able to facilitate these “emotion-affirming encounters” through technological innovation.

Using the innovations of design, medical and health professional, and the arts, Gotsis works to develop platforms which include VR and AR, among other technologies, to help people with afflictions. It is her collaboratory nature that produces innovative products to help with complex health problems. An example Gotsis showed was a shoe that was embedded with sensors that is connected to headphones. Depending on the speed and the actions of the user, the user hears ocean sounds from either outside of the water or from deep in the water. This simulation is helpful to work with patients with balance disorders and for gait rehab.

Though Gotsis’ started in painting and drawing she branched out to interdisciplinary work. She said she was always exposed to technology and even worked at an IT company early in her career. She found that any one academic area does not have the monopoly on creativity--it takes place in any area. As a teacher at USC, she said it is good to have less disciplinary boundaries. Her current goal with her center to is gather lots of different people from lots of different disciplines to attend to bettering human life. She remarked that collaborative work between artists and scientists works better when all are brought in and respected for each of their respective areas than when it is set up as a scenario where an artist seeks and engineer or visa versa. Bringing all disciplines to a table to initiate a goal leverages each participants scope and approach to problem solving.

Gotsis work is exciting and beautiful to experience with the added benefit it can be palliative as well as moving.

Emerging themes for this year are listed below and projects will shift and develop during the Pop-Up, that’s the fun and the discovery. Our Carmen site has full descriptions and space for discussion and you can follow updates @accadatosu and on humanetechosu.org

Future Companions:

Physical Computing for Wellbeing, Assisted Living, Companionship, and Meaningful Social Connection

Research Leads: Alan Price (Design), Claire Melbourne (Dance) and others

Creative Facilitation:

Fostering Wellbeing and Collaboration through Arts-Driven, Emergent Processes

Research Leads: Rick Livingston (Comp Studies), Peter Chan (Design), Ben McCorkle (English)

Art of Relevance:

Participatory Performance, Design Fictions and Virtual Worlds for Meaningful Public Dialog

Research Leads: Marc Ainger (Music) Alex Oliszewski (Theater), E. Scott Denison (Design), Skylar Wurster (Computer Science), Margaret Westby (Concordia) and others

VR and Forms of Care:

Virtual Reality and Games for Wellbeing, Mindfulness and Compassionate Care

Research Leads: Vita Berezina Blackburn (ACCAD), Alex Oliszewski (Theater), Kevin Bruggeman (Design), Susan Melsop (Design), Dreama Cleaver (Design), Laura Rodriguez (Dance), Elizabeth Speidel (Champion Intergenerational Center), Scott Swearingen (Design), Marientina Gotsis (USC, Games for Health), and others.

Our partnership with the Champion Intergenerational Center and the College of Nursing remains a resource and an opportunity for all themes. ACCAD’s Norah Zuniga Shaw, Matthew Lewis and Maria Palazzi as well as the Humane Tech Student Fellows and ACCAD GAs will move between and contribute to all projects and we encourage everyone to circulate throughout the week.

The Collaboration for Humane Technologies seeks to foster interdisciplinary awareness and skills and conduct arts driven research into technology in service of well being on the planet. An important branch of this research is the inclusion of student research fellows. Fellows propose a relevant project or indicate interest in contributing to one of our active projects and become part of our research community by participating in events and engaging with faculty throughout the year. Events can include attending and participating in sandbox collaborations, guest workshops, and engaging meaningfully in our spring Pop-Up Collaboration. Below are some selected research statements and questions from our 2018 Well-Being fellows.

My first thoughts on research about dementia was to make a documentary about my experiences as a caregiver to my mother. But I was also interested in showing her side of the story. How did she feel? What could I show to an audience that would help them understand what it was like to have dementia or care for someone with dementia? Could understanding help create better care for the patient which would improve their quality of life? Realizing a live action documentary would pose many problems I turned to animation. Using animation as a way to juxtapose reality and the confused state of dementia showed potential to me and I created a snippet story using real audio against animated footage of what represented the repetitive symptoms from memory loss.

The main issue with this approach was the audience was still disconnected from the experience. How much information about dementia prior to viewing did they need to understand what was going on in the film?

I thought about an interactive tool, such as a website with game like qualities, which could play with the user’s sense of reality. For example, the user is asked to find the banana and they select an image of a banana but then they are told they are wrong and the image they selected is changed when they see it again. This would continue through levels (stages of dementia). My intention was to work toward using this with actual caregivers, as a training tool within care facilities or the home, in order to increase their knowledge of the needs of the patients.

When I entered Alex and Vita’s VR class I saw the opportunity to develop this idea through VR. What appealed to me in this class was the idea of a live person interacting with the user. This created a personal approach, such as a documentary with story, and a guide through the experience, which could help with understanding. It had potential to create an element of personality for the user by seeing objects and images they could relate to their own lives. It also easily gave the user the ability to experience altered realities without having to “suit up” as in the examples of Alzheimer’s simulations I have seen in the past (see links below). And an easy “out” if they felt scared or uncomfortable with the situation. In the previous Alzheimer’s simulations, the user’s hands are bound, they are blindfolded, and walking around in a real space which has potential to cause injury if they run into an object. My Dementia Experience in VR proposes to create a safer space for the user to explore.

After witnessing users in the prototype for the Dementia Experience as the patient, I saw potential to extend the experience to caregivers or friends of those with dementia to explore other perspectives. I would like to review the original script and pull out more ideas that may be possible to add into this prototype (due to time constraints and technical difficulties some ideas were left out). It would also be beneficial to do more research into what are the most common symptoms that those with dementia are experiencing? Are there symptoms across the stages that could be addressed in this experience? How can the Dementia Experience be beneficial to those unfamiliar with dementia but are facing a diagnosis for themselves or loved one?

Roughly 44% of Americans suffer from chronic stress according to the American Psychological Association. This means that nearly half of Americans are increasing their risk of heart disease, depression, weight gain, early aging and more each and every day. When thinking of ways to cure chronic stress, I tried to think about ways that chronic stress is being approached in the world today. This brought me to research about mindfulness and meditation. The goal for my project up to this point was to create a virtual experience in which an individual could be taught how to meditate, in an environment that promotes meditation. The project took form as a guided meditation session in a virtual reality simulation taking place in a Japanese Zen temple. These temples were places designed for meditation and mindful thinking.

The end of my first year project was seemingly a success, but I began thinking “What can the VR world provide that the real world can’t?”. I wanted to utilize the seemingly endless possibilities of VR to help individuals become more mindful and aware.

The direction I am going right now is divided into three experimental projects. First, with the help of Skyler Wurster, we have developed a way for the virtual world to be able to detect and react to the heartbeat of the player. The intention, at this point, for this simulation is to allow the user to focus on their heart beat by having it control the adaptation of the environment around you. The senses involved in this effort are, sight, hearing, and feeling your heartbeat all around you in this virtual simulation.

The second project will be working with Emotive(EEG) headset. The intent with this technology is the ability to visualize emotion. The Emotive(EEG) headset has the ability to detect different brainwaves and can output that data in a way that can be transferred into the virtual world. I intend to develop a way for an individual to be able to not only see the visual effects of their emotions, but also be able to recognize and control their emotions as well.

Finally, the last project I want to explore is a way to create a user driven experience using the player's breath. The concept for how I wish to utilize this method is still under development. One way that this method is being utilized right now is by the creator of Deep VR. Please follow the link for an understanding of how they use breath as a mechanic in their gaming experience: http://www.exploredeep.com/#about-deep.

The purpose behind this last experiment is to get the user to focus on their breath. Being able to look inward and focus on your breath is one of the most important concepts in meditation.

I am excited to be a contributing student fellow to the Humane Tech Well Being project this year. Having participated in some sandbox collaborations in Norah’s Multidisciplinary class last spring, I will continue to explore and brainstorm creating situations, strategies and environments which facilitate creative collaboration in an interdisciplinary format with students and faculty in the Humane Tech Group. I want to consider who speaks who acts and why, and experiment with and discuss what kind of scaffolding supports greater collaboration, risk taking, follow through with ideas of parallel and mutually supportive process and product.

A project that I would like to connect to the Well Being theme this year is using fort building, with household materials, dance-making and some Isadora patches as entry point for investigating sense of interiority, boundaries and permeability in the body and in the material and digital world. I’m considering how boundaries are an important element of care for self and others and also how a desire for structure, fit and sense of place can manifest in blocking or keeping out otherness. In response, I'm curious about other ways this desire can be nourished that are playful, expansive, evolving and inclusive.

Right now, I am working with 4 other dance students, two MFAS, Brianna Johnson and Kat Sauma, and two BFAS, Lauren Garrett and Emily Kilroy, developing movement and building scores that are stimulated by arrangement of objects as well as interactive sound and video elements, affected, through use of a Kinect and other computer sensors, by human movement choices. I am pulled between two focuses on our individual bodies and sense of limitations and boundaries there both physical and psychical, but also the sort of force fields or insider environments we create and delimit to share with others and the potential for this to create an expanded and shared sense of interiority. What might that extend into as far as greater mutual care, empathy and by extension critical thinking and action? An essential follow up to what I'm working on right now is having this practice extend to a larger public, theorizing and playing with limits of the body beyond the context of contemporary dancers here at OSU.

During the Autumn of 2015, as an incoming Freshman, I became the student curator of OSU’s Andean and Amazonian Cultural Artifact Collection, under Dr. Michelle Wibbelsman’s direction. The collection was acquired by the Center of Latin American Studies with Title VI Federal Funds and is permanently housed in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese in Hagerty Hall. In addition to skills learned from my Arts Management major and History of Art minor, I brought to the collection cultural sensitivity from my Ecuadorian cultural heritage and, as a child of the tech boom, an understanding of a new generation of students, their interests and learning orientations.

Professor Wibbelsman and I have worked together to catalogue and organize the physical display of the artifacts. In addition, we developed interactive digital features, including a digital story map and digital narratives, to support the curated exhibit. Beyond providing contextual information for the items displayed, one of our main concerns was how to give access to artifacts that were too fragile to bring out of the display cases for hands-on workshops. We were also focused on platforms that allow students to interact in meaningful ways with the collection.

In spring of 2017, ACCAD invited our participation and enabled the use of photogrammetry to create digital models of select artifacts. Through this unique collaboration I was able to familiarize myself with new software and the process of creating 3D models. With the help of Jonathan Welch, graduate student at ACCAD, we created 3D digital models of two items in the collection. I presented the outcomes of the project in the ACCAD Open House on April 7th, 2017.

The invitation to join the Humane Technologies Discovery Theme formally as a Research Fellow this year will allow me to continue working on 3D models of our artifacts. In addition to uses for the exhibit itself (including a pop-up traveling exhibit we’re working on), we’ve been invited to include these models in an experimental virtual reality environment called Method of Loci.

For the fields of Arts Management and Policy, a crucial question is whether and how audience members interact with a particular piece of art or interactive exhibit feature. I am curious to see how the features I work on in the context of the Humane Tech Theme engage the audience. Is their experience positive? How do we measure that? Do these interactive features provide an added experience with the exhibit that other features do not? Another research question I have is whether these features make our audience come back again, and/or also whether they might be sharing these features through social media with their friends?

With these questions in mind, I plan to use the fellowship time to create two or three more models of select artifacts by the end of the autumn semester. Dr. Wibbelsman and I will also be working with OSU Libraries Knowledge Repository to permanently house URLs for the interactive features in order to preserve them for future uses. We are using go.osu.edu for tiny urls and generating QR codes that make the features easy to access with cell phones and other personal devices and can track number of viewers.

My thoughts have been over stimulated with impossibilities that keep expanding. I am currently interested in the information surrounding VR, projection, interactive spaces, environments, movement-based VR, and 3D renderings. I am not sure which question I will fully surrender to just yet, and if the subject relates to choreographic research, interactive spaces, or creating a personal experience - or all. More brainstorming for now.

In another work, I made an interactive installation that could be added to with audience contribution over a months period. The audiences that came to the museum could contribute, change, or take away something. These examples while related to the dance field have left me curious for continued information on the merger of space, collaboration, and the technological - human subject.

Back to the ideas for this project. I am going to flush some out here since I do not know what is possible at this stage.

Well-being overall for me generates a partnership between human and machine that enhances life for all people. So much of technology today feels direct in the amount of time lost in the day. Creating something with technology that gives back, supports, or challenges the conventional knowledge surrounding this void seems like a radical act.

Ohio State's College of Arts and Sciences presented a fantastic interview with award winning animator Chris Landreth along with professor and principle investigator Norah Zuniga Shaw ahead of his workshop and public screening along here at OSU. Find a snippet below and the entire article here.

Landreth's master class

"A recipient of multiple honors — including an Oscar for his breakthrough 2004 animated short Ryan — and the progenitor of Making Faces, a groundbreaking course on facial animation, Landreth is one of the most influential animators working today. In advance of his visit, Norah Zuniga-Shaw, professor and director of Dance and Technology and the principal investigator for Humane Technologies research, spoke with Landreth about his work.

Norah Zuniga-Shaw (NZS): I’m excited to talk with you about your upcoming residency at OSU/ACCAD and what “humane” might mean in relation to your work. First and foremost you are a storyteller, and the stories you tell are humane in the way you use computer graphics to reveal people’s inner lives. You address issues of addiction, marital dysfunction and grief in your work in nonjudgmental ways.

Chris Landreth (CL): You’re talking about The Spine and Ryan, probably. My ultimate goal is to tell a really great story, and the best and easiest way to tell a really great story is to tell it with empathy. In order for the story to succeed, I have to create a sense of empathy for the audience to have a way into the stakes of the story. The nice thing that comes out of that — at least I hope — and I’m glad that you picked that up, is that there is a sense of compassion and caring. "

Jan.2 saw a fabulous article about a fabulous artist, Michelle Ellsworth who was here at OSU for a week this fall as one of our guest artists for humane technologies performance research. I suggest this article as a great read for anyone needing to feel better in this new year and to find ways as Seth Godin says to "stretch in whatever we do to be artists, to create in ways that matter to other people." Michelle's work makes me feel like there really might be something I CAN do as a dancer, an improviser, an artist, teacher, human: "Like many people over the past year or so, Michelle Ellsworth has often felt disoriented, as if the world had been turned upside down. But she is probably the only person who responded to that feeling by putting herself in a wooden wheel so that she can be rotated 360 degrees around the axis of her nose." Michelle was an incredibly galvanizing presence, cutting through all the mishmash with humor and her own electric presence. We are still enjoying the catalyzing effects and her directing changed the pathway of our performance research projects in powerful ways. Because of her directing, the piece we are creating with the laptop orchestra has become an overt expression of the precarity we are experiencing with the impacts of climate change in our lives. Stay tuned for more on that piece "A Lecture on Climate Change."

Read the full New York Time article

On October 27, 2017 Norah Zuniga Shaw hosted a writing jam in relation to this years theme on Wellbeing entitled Beautiful Complexity. This jam included a movement storm which is a score for generating ideas, developing language and getting into a shared space of embodied discovery. Below are selected reflections from participants Candace Stout and Ben McCorkle.

Last week Norah invited me to a sandbox, along with our good colleagues Peter Chan, Ben McCorkle and Rick Livingston. I envisioned a think-tank affair, four of us seated around a table, Norah flipping a tablet, noting concept gems, diagrams and ah-ha moments. Things, however, weren't that way and at the outset, I was uneasy. Maybe it was the Starbucks venti espresso. Maybe it was the walk through the ACCAD supply closet culminating in a rubberized room, or the almost audible monastic soundtrack infusing that space. Whatever was that initial instinct [over-caffeination or sedimented institutional expectations], it dissipated in finding, in Toni Morrison's words, "the friends of my mind." Among the piles of yellow paper scattered on the floor, the incidental flip charts at the edge of the room, and in the layers of journal articles that Norah placed on tables, I found compelling relevance. There were key words, incisive phrases, and insistent commentaries-expressions resonating with and informing my own humanizing epistemology and practice, and importantly, that of my grad students in the most consequential ways. Humanizing research works toward connection and disruption, relational, dialogic, consciousness-raising for self and others. It is a mind-set, strategies animating and probing performance and experience, activating sympathetic and empathic awareness. Graduate researchers in my writing seminar use the virtual to examine, understand and impact the material-the real. They are committed to the work of

meditation for well-being, healing, coping with the human condition; understanding the nature and import of embodied knowing; using arts performance as connection in public spaces; using narrative ways of knowing for the researcher-self and those with whom meaning is created. Multimodality in knowing and relating are primary in what they do. Research toward connection, disruption, and resolve. Thank you Rick, Peter and Ben for this collaboration. Thank you Norah for sharing this inspiring box of sand.

I’d like to play with a scaled-down version of a much larger cloud of ideas that I have percolating in my head that deals with generating creative ideas by exploring connections between binaries, closed systems, things that seem irreparably divisive, unconnected, or incapable of change.

The jam activity today was designed with a particular purpose in mind: to generate ideas that will guide the HT collective’s thinking about the theme of well-being might eventually help give shape to some future artifact or text such as a journal article, blog post, etc. After debriefing, we first engaged in a 20-minute period of “graze, gather, raise.” After, we shifted to the atomizing phase, exploding a concept out into multiple areas, then shared our results with one another, and then left to produce things like this one I’m writing now

Yes, I know, we were all there—your recollection is probably a lot more granular than this account is. My point, though, is that everyone talked about the *process* of this activity—we acknowledged it *as its own thing* rather than the thing that leads to the thing (i.e., that piece of writing, etc. that we might generate down the line). Process and product—this is how we typically butcher the meat. But in this case, the process itself can be seem a type of product, a thing in and of itself, or at least the anticipatory echo of products-to-be. Here, I find myself contemplating what that means in terms of the HT project and how it relates to this theme of well-being. This process-as-product, which engaged the entire sensorium, our sense of proprioception, our sense of care as we moved through the space and manipulated its contents, opens up a space of possibility as a potential product that addresses our idea of well-being.

For example, I can imagine this activity as an immersive VR program designed to help users generate their own creative ideas that allows them to map, move, (re)place text, images, etc., and especially allow for positive collaborative interactivity. Or maybe some sort of meditation training app that, by moving words rapidly, playfully, and constantly through a virtual or augmented space, creates that mantra-like phenomenon of semantic satiation that often accompanies transcendent states (“care, care, care, care, care, …”). Or maybe an application that would help with conflict mediation in some way by creating a dynamically manipulable, shared virtual space where users would work with material in a way that would bring about resolution through cooperative play (okay, this one is a little half-baked, but I think there might be something there). In these cases, the underlying idea is the same: focusing on today’s process itself as the wireframe around which we build possible products aimed at designing technological solutions to the problems impeding our well-being…

As part of the ongoing Humane Technologies investigation at ACCAD at Ohio State, guest artist Jennifer Monson presented a lecture the evening of April 11th, 2017. Monson also led an experiential "dawn walk" the same morning on the OSU Oval for thirty interdisciplinary participants.

Monson’s attention to environmental phenomena incorporate Humane Technologies greater mission of sustainability. Her work is also deeply embedded in interdisciplinarity as her research “upholds a fundamental commitment to environmental sustainability as it relates to art and the urban context and cultivates cross-disciplinary research among the arts, environmental science, urban design, and other related fields.” Monson’s studies also look to reimagine humans relationship to the environment and the places they inhabit.

Photo by Valerie Oliveiro

Jennifer Monson is a choreographer, performer, and teacher. Since 1983, she has explored strategies in choreography, improvisation, and collaboration in experimental dance. Through multiyear creation processes, her works have investigated animal navigation and migration (BIRD BRAIN, 2000-2005), human impact on natural sites (iMAP/Ridgewood Reservoir, 2007), and communities in east-central Illinois dependent on the aquifer (Mahomet Aquifer Project, 2008-10). In 2004, Monson incorporated under the name iLAND (Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Art, Nature, and Dance), which explores choreographic, improvisational, and collaborative strategies in experimental dance. Monson is currently a professor of dance at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Marsh Professor at Large at the University of Vermont. Her current work-in-development is in tow, which investigates the nature of collaboration and experimentation across geographies and disciplines.

Rosalie Yu's work engages in the creation of meaningful social connections through 3D scanning and photogrammetry. Yu spoke in her artist talk about projects such as Embrace in Progress and her research into creating lasting artifacts from fleeting moments of intimacy. The use of this technology and it's compassionate creation methods is integral to the Humane Technologies project.

Yu came to ACCAD as a Visiting artist and scholar to conduct a hands-on workshop on depth photography and photogrammetry, and how capturing the depth axis can further unfold the real world and create new perspectives. She posed the following questions in the beginning of her talk: How do machines capture emotion and time? How can an artist capture intimacy? In what ways can we represent organic human qualities in digital mediums? Yu shared her past research Embrace in Progress as well as Skin Deep which investigates these questions.

In the workshop, Yu demonstrated how to use the 3D scanning tool Skanect to create models using an Xbox 360 as the scanning tool. Scanning reconstructs a point cloud of the object, creates a mesh to surround it, and applies textures- similar to other 3D scanning softwares. The act of scanning is an physical task since the person needs to move slowly around the body while keeping the sensor horizontal and moving up and down in space to capture the entire body. The resulting scans were uploaded to the website Sketch Fab and Yu suggested extra resources for future endeavors in this work such as 8i, Mesh Lab, Mesh Mixr, and Net Fab, and itSeez3D.

Rosalie Yu is a creative technologist from the Brown Institute for Media Innovation at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. Ms. Yu's visit was sponsored by the Humane Technologies Project, of the Humanities and Arts Discovery Themes at The Ohio State University, Advanced Computing Center for the Arts & Design (ACCAD). She works with emerging photo- (depth photography, photogrammetry) and 3D-technology to capture and transfigure everyday experiences.

Humane technologies do no harm, they are creatively open-ended, socially connected and access the full multi-sensory capacities of human intelligence. Humane tech creates compassion and well-being, embraces complexity, enhances collaboration and is radically inclusive. With these humane working assumptions, the 2017 Humane Technologies Pop-up focuses on livability in the 21st century.

From March 6- 10, 2017 ACCAD faculty, staff, GAs and many of our classes worked on creative projects in the working space of a hack-a-thon or a charrette the purpose of this week was to create a focused time outside our busy lives for creative collaborative action. Students from the environmental humanities and human rights research groups joined us as well as alumni guests who are taking time out from their work at google, Adobe and in their own design firms. All of our working spaces (the open collaboration rooms, SIM lab, Motion Lab, conference room...) were utilized in the sharing and documenting the prototypes and artworks and advancements made together.

This ongoing project investigates the application of immersive theatre and improvisation based devising methods in the development of room scale virtual reality experiences.

The projects allow a participant to put on a Vive head mounted display and interact with a virtual avatar performed by a live actor and a virtual environment in real time. Each environment is associated with a rough story idea. The participant can improvise interactions and dialogue with the live actor. Some variations of this setup also introduce an additional character pre-recorded/captured by the same or another actor. Most environments include physical props that match locations of some virtual objects, creating a possibility of haptic feedback. With attached optical markers, some of the props are also physically manipulatable. Through this work we seek to gain better understanding for developing innovative VR experiences that involve co-presence and cooperation among multiple participants, haptic based on real objects with the foreseeable applications in the arts as well as education, various types of training and multi-player simulation.

The technical setup takes places inside a 40x40’ volume with 20x20’ trackable area and a projection screen for the audience and the actor. Physical furniture and props provide haptic feedback for the participant. Besides the furniture and the screen, spike tape marks on the floor guide the actor. We combine optical tracking of the live actor and physical props with HTC Vive headset and controllers tracking via the lighthouses. Vicon Blade in combination with Unity 3d or Motionbuilder is used for prototyping and developing the experience. Immersive sound is optionally used in the experiences allowing the participant to hear actor’s voice through headphones as they speak through wireless microphone.

Interdisciplinary artists based in Tel Aviv, Ohad Fishof and Noa Zuk joined the Humane Technologies team of collaborators at OSU in arts-driven research investigating 21st century life and livability. Zuk & Fishof have collaborated for over a decade and work in a diverse range of fields including Dance, sound performance video and installation. In February 2017, they participated in group discussions and Fishof gave an artists talk.

By Michelle Wibbelsman

Humane Technologies Discovery Theme

In Spring of 2017 I was invited to join the Humane Technologies Discovery Theme as a research fellow from the Humanities. My area of expertise lies with Latin American indigenous cultures, epistemologies, and performance practices, particularly those of the Andes and Amazonia, which have unique perspectives on technology, humanity, livability and wellbeing.

In Ecuadorian Quichua, sumac kawsay (also spelled sumak kawsay or sumaq causai) captures the essence of meaningful, beautiful, proper living and connotes a sense of “livability.” In indigenous worldview, making things knowledgeably and beautifully is conducive to meaningful and proper living, as is personal and collective reflection by way of oral traditions, participatory practices and indigenous art. Another key aspect of sumac kawsay is the practice of sustained dialogue, mutual nurturing, and exchange based on relations of respect and cariño (affect).

Aside from the ethics of good, proper living, people often frame meaningful, beautiful living in terms of an aesthetic defined by zig zagging and a back and forth movement (quingushpa), evident in weaving, music, poetic linguistic patterns, dancing, pottery designs…and pretty much everything else as a recurring and reiterating pattern. At the height of its expression, this aesthetic reflects mastery of a sense of playfulness between symmetry and asymmetry. In contrast, being too direct or going straight to the point is considered yanga puringashpa (following an ugly and aimless path) be it in artistic expression or cultural habits such as speaking too directly, not using enough suffixes, ending a conversation too abruptly, conducting a financial transaction without engaging in pleasantries, doing or making things without embellishment, knowledge and sensitivity…

When people state that they live “always talking, always conversing with one another” in this quingushpa sort of way as part of sumac kawsay, more than signaling a cultural practice, they are underscoring a rhythm or style of going about life. Moreover, they are not only referring to a human community, but to a sustained conversation with beings in other time-spaces or pachas as well. The Andean indigenous world has four pachas: the world above (hawa pacha) where all kinds of spirits and syncretic divinities exist, “this world” (kay pacha) which is the world of nature, “the fourth world” or “the other world” (chusku pacha or chayshuk pacha) where the ancestors live, and uku pacha which is the world below or more precisely the world within where people live. I outline these pachas in my book Ritual Encounters: Otavalan Modern and Mythic Community (2009) and argue that they are not theoretical or folklorized notions, but instead a fundamental part of people’s daily reality.

Obligations to other people in terms of respect, dialogue, exchange, mutual nurturing, conviviality are similar to those with beings from other time-spaces. Animals, plants and things are often referred to as runa (literally, fully human being—the self-designator of Quichua ethnic communities). The Earth, for instance, is pachamama, Mother Earth, and is treated with the respect and sensitivity due to a mother. The animated landscape, with gendered qualities, embodies ancestors referred to as dear great grandparents. Saints as well as animals, including plague animals and insects, are treated with cariño and brought into a relation of compadres or fictive kin. Many agricultural techniques rely on dialoguing with the insects and listening to the signs of nature. The souls of the deceased are kept alive through frequent visits to the cemetery. Without food and conversation, indigenous people say the souls would die for real, (like the mestizo souls since no one visits them)…

All of this to signal that notions of “humanity” are much more inclusive in the Andes. This in turn changes the way people relate to their environments from the hierarchical arrangement that puts people on top in the Western conception (and justifies exploitation of the environment as a resource for people) to a less hierarchical, more reciprocal system where people are on par with other beings that share their humanity.

Andean technologies work with nature rather than trying to go against it or dominate it. We see this in the impressive Inka stonework where each piece is tailor-made to work with elements in its environment.

Similarly, people say that they do not try to eradicate pests or cut out diseases, but rather to dialogue with them, understand their needs, find a compromise that allows everyone to live well—a radical redefinition of the “common good.” They do not try to force production, but rather respect a healthy pace of production, including rest periods. Value is not defined by maximizing profit and accumulation but instead guided by principles of redistribution. This marks a significant difference from Western practices in agricultural techniques, medicine and healing.

This attention to relations of mutual nurturing with the environment also points to a vision of long-term commitment with nature, and with humanity. The future is defined not in terms of immediate gain, but rather sustainability along a millenarian timeframe. It seems that time and sustainability must necessarily be a factor in defining humane technologies and livable futures. As I traveled through the Sacred Valley in southern Peru in summer of 2017, I was impressed by the fact that Inka and pre-Inka constructions and technologies endure—structures are intact, the Great Inka road continues in use, aqueducts are functional, agricultural terraces are in production. In the meantime, earthquakes have devastated colonial and modern constructions. Remnants of electric and gas-driven mechanisms, pipes, modern roads lie abandoned and in disrepair alongside technologies that are more than 500 years old and perfectly functional. Modern agriculture has turned once fertile fields into deserts due to overuse of fertilizers, herbicides and gm crops not endemic to the region. The flower industry in northern Ecuador is one such example where as one glances across the landscape one can clearly see how corporations simply move to another plot of land once they’ve exhausted the previous one. 20th and 21st century technologies do not appear to have improved on Inka and pre-Inka engineering.

The idea of a shared humanity with other living and also nonliving things opens a space for thinking about nonhuman ontologies (or perhaps now that we’ve defined human more broadly, ontologies not exclusive to people). My sense is that the recognition of and engagement with other ontologies is where the rigorous theoretical work begins to decenter people in a conceptualization of humane technologies.

I hope the synopsis above does not present an overly simplified impression of concepts and practices that carry important depth. The notion of sumac kawsay, for instance, has made it into the 2008 Ecuadorian constitution as a recognition of indigenous values and principles. At the same time, its complexity has been reduced in the Spanish translation buen vivir (good living) and by way of this simplification the concept has been coopted by the State to reference the common good in terms of the duties of the Welfare State within a capitalist economy. This is quite different from the understanding, lived practice and context of sumac kawsay, the common good, and well-being in indigenous communities.

As we collectively turn to a renewed attention to topics of livable futures, humane technologies, and well-being in the midst of growing inequality in our societies and escalating concerns about our global environment, indigenous cultures may have something important to contribute to the discussion by way of the radical alternatives they put forward.

Scott Swearingen (Design); Scott Denison (Design); Ben Schroeder (CSE); J Eisenmann (CSE); Kyoung Swearingen (Design); Matt Lewis (Design); Norah Zuniga Shaw (Dance); Chris Summers (Dance), Alan Price (Design); Isla Hansen (Art); Alex Oliszewski (Theater); Oded Huberman (Dance); Sarah Lawler (Design). Demo Location: Motion Lab (room 350). Digital + Physical Games

This project involves development of a framework that explores, discovers, and questions the intersection of physical and virtual presence within the context of games. While ‘play’ offers the individual an opportunity to learn about themselves and others, ‘games’ provide the necessary structure to make our choices meaningful and give weight to our capacity for empathy. Furthermore, by integrating physical and virtual presence in this framework, we can streamline our ability to abstract relationships within a given system, and hence, one another.

A playable prototype of a two-player game using Kinect/ Processing and Unity. Players cooperate to navigate a scrolling landscape, dodging or otherwise moving around emerging obstacles, barriers, and projectiles.

We created this in a week during our Human Technologies Pop-Up intensive. There was never a time throughout the week that we were worried about having a deliverable. Keeping the mechanics simple and having a really small design footprint helped us stay agile, and made development easy to pick up and put down. Investment was also key. We wrangled faculty, students, and staff for their ideas, and bounced our own off them for hourly sanity-checks.

Method of Loci (a mnemonic system in which items are mentally associated with specific physical location) Alan Price (Design); Isla Hansen (Art); Scott Swearingen (Design); Norah Zuniga Shaw (Dance); Michelle Wibbelsman (Latin American Indigenous Cultures); Ben McCorkle (English). Demo Location: SIM Lab.

We set out to explore modes of interaction between users immersed in VR with a Head Mounted Display, and users with an external, third-person perspective using a multi-touch display. The design intent was to draw awareness to the differences in scale and perspective, engaging users in a process of collaboration that requires navigation and communication across the two modalities and encourages awareness of both digital and physical experience.

The current outcome is a networked multi-user VR collaboration space that encourages experimental making and play through collective creation, assembly, and recording. A mobile web app is used to upload images, sound, and video, as well as 3d models, in real time, to contribute to a growing and malleable virtual world. Inside this world, users can move, combine, and attribute physical properties to objects, videos, and sounds. Recording these movements, users can create animations, drawings, and spatial soundscapes. Objects take on meaning through the users’ intent, creating associations through composition and movement in the virtual space. The system can be used for staging games, collective sense-making, storytelling, or other purposes to be discovered.

Critical thinking and research in the domain of humane technology can include ongoing study of the design of interfaces; the design of modes of interaction; the design of technology that can enable us to freely converse between physical and digital constructs. Developing systems that promote reflection by its users on how we understand our engagement with systems and how we can engage with one another through a system, benefits from focusing on the attributes that support or expose a deeper dialog about the mechanisms operating to enable that engagement.

Birdbot flyover: flap your arms to drift over various compassionate landscapes as conceived and created by students in Design. Norah Zuniga Shaw (Dance, Principal Investigator); Alice Grishchenko (Lead Designer); Isla Hansen (Art); Maria Palazzi (Design), and students in Palazzi's Design 6400 class: Breanne Butters, Stacey Sherrick, Sarah Lawler, Zachary Winegardner, Kevin Bruggeman, Devin Ensz, Bruce Evans, Dreama Cleaver, Kien Hong. Demo Location: SIM Lab @ accad.osu.edu.

Birdbot balance: Rise through virtual woulds and make music with your wings as you achieve balance challenges in VR: Norah Zuniga Shaw (Dance, Principal Investigator); Alice Grishchenko (Lead Designer); Isla Hansen (Art); Maria Palazzi (Design); Demo Location: SIM Lab @ accad.osu.edu.

Get moving in VR! BirdBot grew out of an early Sandbox Collaboration we had using the Kinect to get good full-body interaction in virtual reality (rather than just being able to move or play with things using controllers). It is also a response to one of our core research interests in this project which is to create more physically active and stimulating virtual reality experiences.

The resulting prototype is what we call a "movement toy" and there are a few movements we targeted specifically including "balance," "level changes," and any gross motor action (in this case flapping the arms). But really any desired movement could become a mechanic of this "toy."

We created is a series of Virtual Environments for the Oculus Rift using a Kinect as our sensor. One of our creative interests was to see what happens when we start with a movement idea and let the virtual world grow from there. A movement creates a story and the story creates the world. So it was a very intuitive, emergent process and evolved through many iterations that existed in the collaborative space between our minds/bodies. We had some fantastic brainstorming sessions with visual artist Isla Hansen about making a physical installation to experience while in VR and will continue that going forward. The nature imagery and heron came from our discussions about de-centering the human and making non-mirrored interfaces. When you put the headset on and enter the world of Birdbot you are in a peaceful room with grids on the walls but it is filled with trees and your shadow is a heron. If you flap your arms, a hidden world is revealed and as you balance on one foot (a challenge in VR) you rise up into a bright pink tunnel where you can make music with light-up chimes. Finally you enter a flyover world where you soar over a collage of compassionate landscapes that were created by students in our Teaching Clusters, including a tapestry made up of family photographs compiled from our research team.

As always in the iterative design process, some of the things we tried out but didn’t use provided us with fun learning experiences and make the work stronger. The challenges of computer recognition of particular motions is a long-standing issue but the KINECT has made things easier and it is fantastic to see people moving and laughing and feeling good in VR.

Further relfection by Alice Grishchenko at http://www.humanetechosu.org/humaneblog/2017/5/12/bird-thoughts

Collaborators: Norah Zuniga Shaw (Dance, Principal Investigator); Alice Grishchenko (Lead Designer); Isla Hansen (Art); Maria Palazzi (Design), and students in Palazzi's Design 6400 class: Breanne Butters, Stacey Sherrick, Sarah Lawler, Zachary Winegardner, Kevin Bruggeman, Devin Ensz, Bruce Evans, Dreama Cleaver, Kien Hong. Demo Location: SIM Lab @ accad.osu.edu.

Alice Grishchenko, MFA student in design and a key collaborator on the Humane Technologies team writes:

I loved making Birdbot. It is a virtual world that encourages certain motions, it isn't really a VR game, sometimes we call it a toy. It was a non-linear process to create it. Norah calls that emergent. We started from a place of abstract interactions, prototypes and a jumble of 3D models and textures pulled from many different sources and somehow we ended with a surreal 3 part experience, of which the most visible linking themes are birds and shadows. Personally, I started with some questions like:

Each of these questions is actually a cascade of many other questions that should ultimately be answered by players interacting with the system, but before having those answers you have to create a system by anticipating them. Hypothetical answers are tricky, so I started with some low investment prototypes that looked like this:

The goal was to get the player moving in a fun way by creating an interactive environment. I tested many interactions with physics simulations, flying, floating, and rhythmic movement. I would run these by Norah and we'd talk about the intention compared to the feeling of the environment, and repeat this playtesting process with other collaborators to see what perspectives they could bring. Through this process we created three different interactive environments, then connected them with visual transitions and common themes. Slowly we started to solidify which features we wanted to develop in each scene. The three stages became surreal, calm spaces with strange gravitational properties and shadowy avatars that represent otherness. The levels remain separate in the mechanics of their interactions, balancing, reaching out for virtual contact and flapping arms in a way that imitates flight.

We connected the three levels in a way that creates the experience of moving from an enclosed space, upwards to a vast open space and then forwards into a tunnel that leads back to the beginning of the experience. The content of the levels changes dramatically once the player ascends to the open space. This is because we enlisted the help of Maria Palazzi's class to create compassionate landscapes for the player to soar over. The class's work is combined to generate a procedural world that changes over time. Collaborating with an entire class of people for a week was a really unique experience for me, and Maria's class delivered some great insights and beautiful assets to the work that made it much richer. I worked with Skylar Wurster to develop the spherical procedural landscapes and we used some custom shaders to fade between ground and (sideways) sky textures.

A compassionate landscape/interpretation of how birds may view an urban environment

All these changes between the three levels and all their components provide players with many unusual experiences and sensations one after another. I think the piece really leads the player to think about identity and the journey of connection they just experienced.