Reflection contributed by Dan Shellenbarger

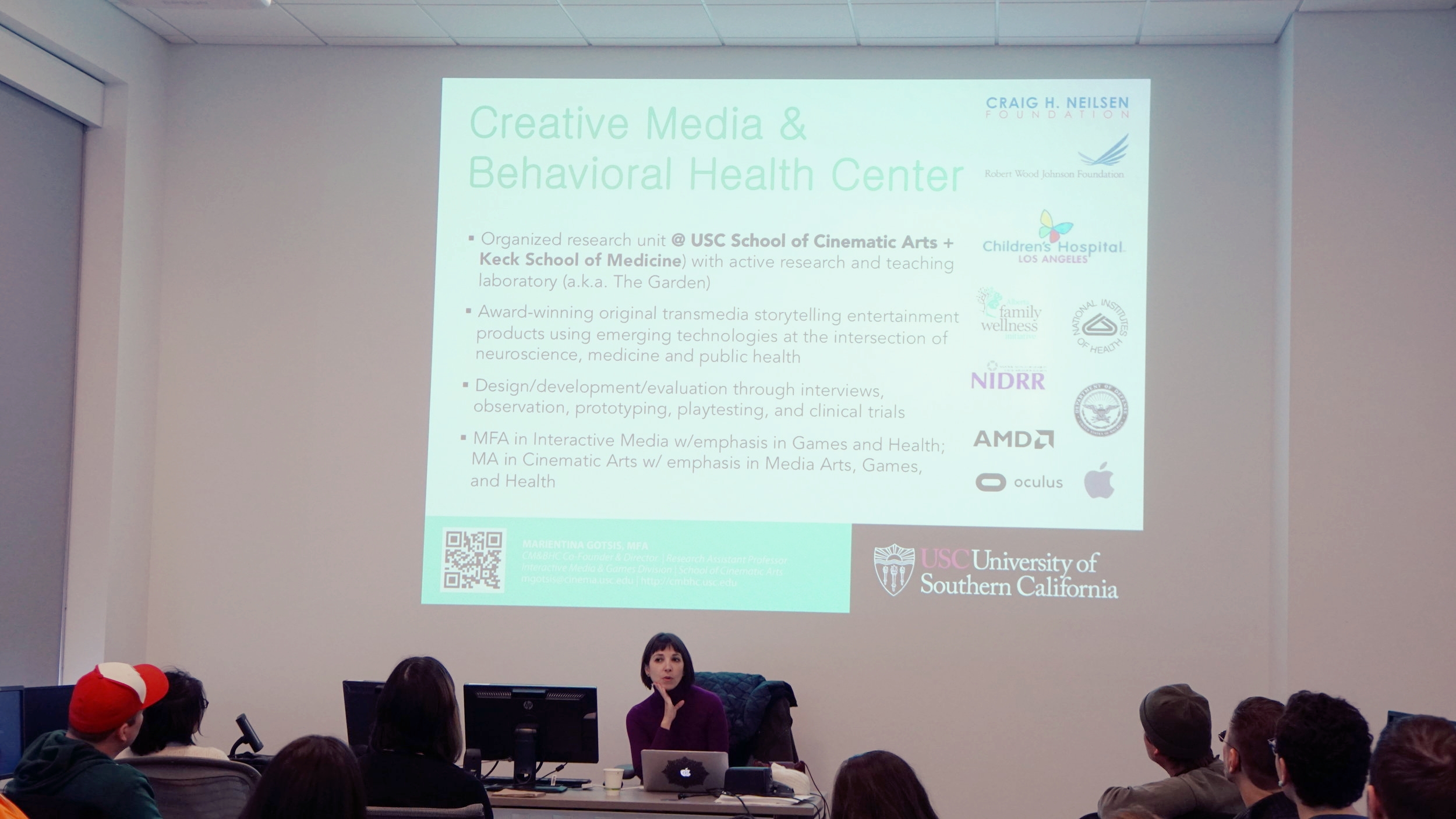

Marientina Gotsis shared her work and research during her flash presentation for the Humane Technologies Conference. She founded and currently directs the USC Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center, where she also founded and directs the USC Games for Health Initiative. Her work involves translating interactive media innovations to health practitioners. She works works to intersect art, neuroscience, medicine, and public health.

She showed projects that were developed to help in the research fields including Parkinson's and mental health. In the area of mental health she share a quote from Jaak Panksepp, a neuroscientist, who provides an inspiration to her work:

“Mental health ultimately means that an individual, through rich emotion-affirming encounters with living, has integrated his or her life in such a way that the emergent self-structures, deeply affective, can steer a satisfying cognitive course through future emotional jungles of lived lives.”

In her work and the work that is developed in the USC center, she is able to facilitate these “emotion-affirming encounters” through technological innovation.

Using the innovations of design, medical and health professional, and the arts, Gotsis works to develop platforms which include VR and AR, among other technologies, to help people with afflictions. It is her collaboratory nature that produces innovative products to help with complex health problems. An example Gotsis showed was a shoe that was embedded with sensors that is connected to headphones. Depending on the speed and the actions of the user, the user hears ocean sounds from either outside of the water or from deep in the water. This simulation is helpful to work with patients with balance disorders and for gait rehab.

Though Gotsis’ started in painting and drawing she branched out to interdisciplinary work. She said she was always exposed to technology and even worked at an IT company early in her career. She found that any one academic area does not have the monopoly on creativity--it takes place in any area. As a teacher at USC, she said it is good to have less disciplinary boundaries. Her current goal with her center to is gather lots of different people from lots of different disciplines to attend to bettering human life. She remarked that collaborative work between artists and scientists works better when all are brought in and respected for each of their respective areas than when it is set up as a scenario where an artist seeks and engineer or visa versa. Bringing all disciplines to a table to initiate a goal leverages each participants scope and approach to problem solving.

Gotsis work is exciting and beautiful to experience with the added benefit it can be palliative as well as moving.